Out

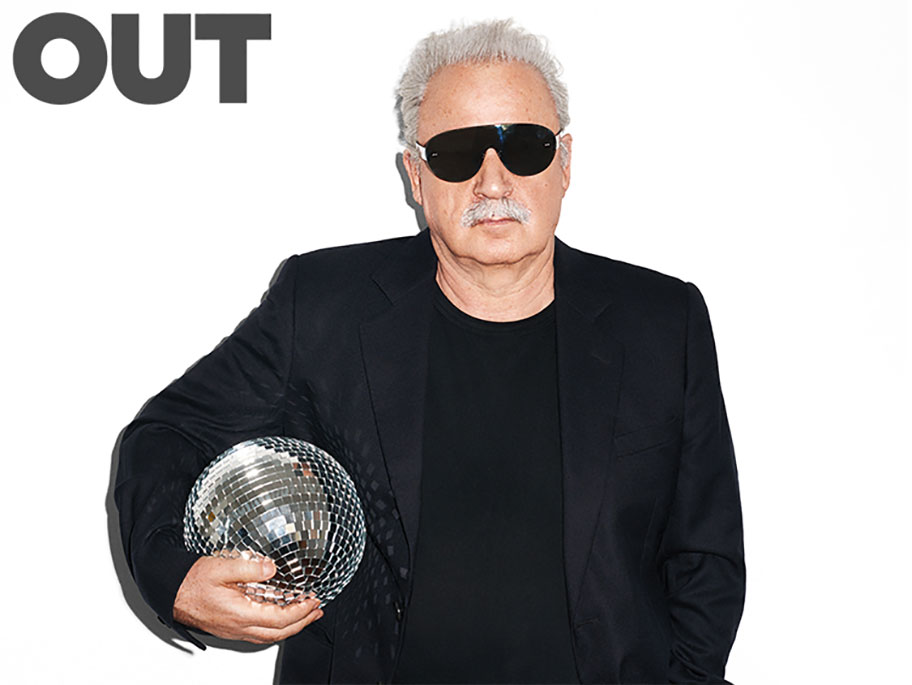

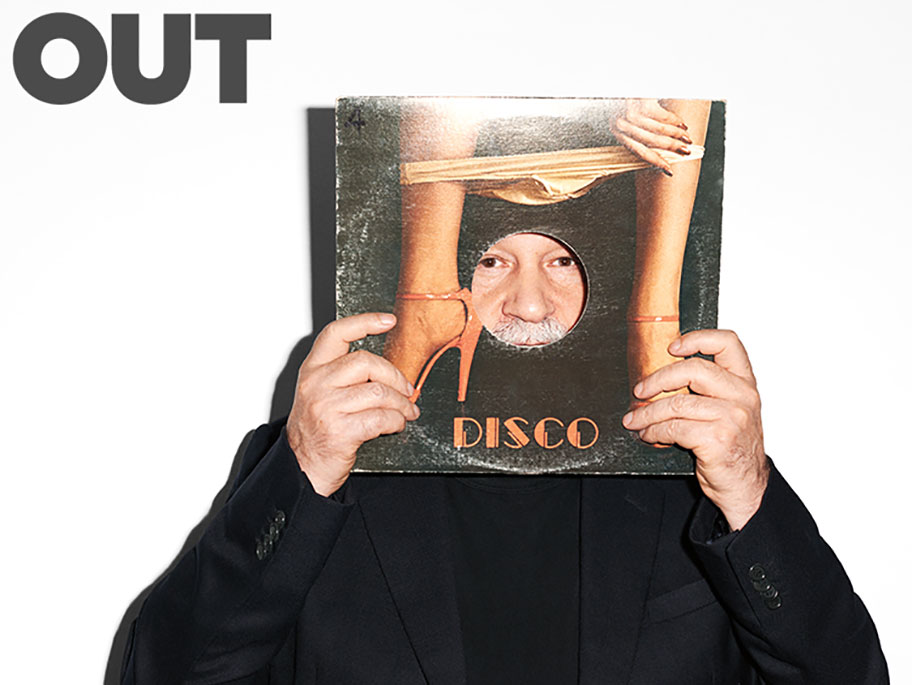

The Comeback of the Summer: Disco King Giorgio Moroder

By Jason Lamphier

Photography by Terry Richardson

May 5, 2015

In his ’70s heyday, legendary producer Giorgio Moroder was unstoppable, cranking out Studio 54 classics for Donna Summer. Now, after a 30-year hiatus — and backed by an army of today’s biggest pop stars — the man who all but invented EDM is preparing the ultimate comeback.

Photography by Terry Richardson. Styling by Michael Cook. Groomer: Andrew Fitzsimons for artists by Timothy Priano. Jacket by Emporio Armani. T-shirt by Calvin Klein. Sunglasses by Giorgio Moroder X RetroSuperFuture. (All clothing worn throughout)

Giorgio Moroder remembers going to Studio 54 only once. It was in the mid-1970s, just after the Italian composer and producer had released “Love to Love You Baby,” his breakthrough smash with Donna Summer.

“I had a driver, and I’d come to the Studio and I’d seen this long queue of people waiting to get in,” he recalls. “I said, ‘I’m not going to wait in the back.’ So I asked the driver if he could ask the doorman to let me in. So he let me in — and it was empty.” He continues, whimpering like a little boy with a broken toy: “I was so disappointed. There were maybe 20, 30 people. It was far too early in the evening, and I didn’t know that the earliest Studio 54 filled up was midnight.”

It’s a chilly Sunday afternoon in late January, and Moroder, now 75, is tucked into a booth in a cozy French café in Manhattan’s SoHo district. The dark, shaggy mane he had at the height of disco is gone, replaced by slick-backed, thinning white hair; he still sports his signature bushy mustache, though it, too, is now white. Wearing a fleece North Face vest over a blue-striped button-down, warmly waxing nostalgic, he looks more like a seasoned comparative literature professor than the prolific pioneer behind some of the most famous and influential dance songs of all time. It’s hard to imagine him getting into — or even wanting to get into — any club, ever.

Once upon a time, Moroder was the most sought-after producer in the world. After the international success of “Love to Love You Baby” and its 1975 album of the same name, he, his producing partner Pete Bellotte, and Summer churned out six more albums in four and a half years, all of which were certified gold or platinum. He snagged an Oscar for his music for 1978’s Midnight Express, and composed the soundtrack for 1980’s American Gigolo, which led to his Blondie collaboration, “Call Me,” the number 1 song of that year.

The ’80s weren’t kind to disco, but they were to Moroder (mostly). He won two more Oscars — for Irene Cara’s “Flashdance…What a Feeling,” from the 1983 film Flashdance, and for Berlin’s “Take My Breath Away,” from 1986’s Top Gun — and also wrote and produced the soundtrack for Scarface and the theme song for the 1984 children’s fantasy The NeverEnding Story. He racked up two Grammys and three Golden Globes, crafted anthems for both the Los Angeles and Seoul Summer Olympics, and, along the way, co-wrote and produced songs for everyone from David Bowie, Freddie Mercury, and the Human League’s Philip Oakey to Janet Jackson, Bonnie Tyler, Cher, and Barbra Streisand.

His tale of his Studio 54 fail is fitting given Moroder’s two-decade-long, on-again, off-again relationship with cool. Moroder’s output was eclectic, ceaseless, and, at times, dubious. He was, perhaps, his era’s most insatiable sonic explorer, the proverbial kid in the candy store, dipping his finger in every flavor. He reveled in disco, of course, but also saccharine pop (his 1969 debut album, That’s Bubble Gum — That’s Giorgio, on which he also sang); experimental electronica (1975’s Einzelgänger); and saxophone-assisted dad rock (the 1986 Kenny Loggins cheesefest “Danger Zone”). For every sublime track — the proto-techno game changer “I Feel Love” — there were more questionable ventures like his notorious 1984 soundtrack for his restored version of the Fritz Lang silent masterpiece Metropolis, anathema to film purists and a project Moroder himself now considers a bit of a dud.

RELATED | The Giorgio Moroder Primer

Yet all this genre-hopping is a key reason Moroder left such an indelible impression on the pop landscape — his influence extends to just about everyone. He is considered not only a chief innovator of disco, but also a progenitor of the synth-heavy New Wave that dominated the ’80s, as well as the hip-hop, house, and techno that followed it. What we now call EDM would arguably not exist if it weren’t for Moroder. His successors include stadium fillers like Avicii, Skrillex, and Katy Perry producer Dr. Luke — all of whom have exalted Moroder’s work — and neo-disco acts like LCD Soundsystem and Chromatics. His music has been co-opted by rappers (Kanye West and Outkast have sampled him) and routinely interpreted by drag queens (who have a particular soft spot for Summer’s 1978 remake of the camp classic “MacArthur Park,” containing one of the most ridiculous metaphors for lost love ever put to record).

As the ’80s drew to a close, Moroder’s star fell. The movies he soundtracked were forgettable, and he didn’t know what to make of the emerging hip-hop so indebted to his work. He remixed songs in the 1990s and 2000s, but nothing particularly noteworthy. He’d all but disappeared — until two years ago, when Daft Punk, two of Moroder’s biggest fans, enlisted him for a song on their retro-influenced comeback album, Random Access Memories. The track “Giorgio by Moroder,” which features samples from an interview in which the producer muses on his discovery of the synthesizer, was a sprawling, nine-minute homage to the granddaddy of modern dance music, a sort of poignant autobiography, and the catalyst for what would be Moroder’s own comeback.

“It’s not only their fault,” Moroder jokes between bites of a croque monsieur stuffed with extra ham. “I’d started DJing, and a record company made me an offer to do an album before, but it came from a guy I didn’t like, so I didn’t pursue it.”

Now, as he prepares to release his first solo record in three decades, Moroder is cool all over again. Titled Déjà Vu, the upcoming LP features collaborations from some of pop music’s biggest stars, including Sia, Britney Spears, Kylie Minogue, and Charli XCX. Earlier this year, he announced that he’s also teaming up with Lady Gaga for her next album. He’s doing DJ sets all over the globe, and is now in talks to score a major full-length feature. He also recently did music for a Google mobile game and a Super Bowl commercial, and nabbed his fourth Grammy for the Daft Punk record, which won Album of the Year.

“That Daft Punk album comes out, is a big hit, and then I got three offers to do albums,” he says, shaking his head in disbelief.

“That is almost unheard of right now.”

It seems Moroder’s influence has come full circle, and he’s arriving to the party just in time.

Born in 1940 in Ortisei, a village in Northern Italy, Moroder learned guitar, then bass, and spent several years playing with various groups throughout Europe before settling down in Munich, Germany. There he founded Musicland — a recording studio later booked by acts like Queen, Elton John, and the Rolling Stones — and released his 1969 debut single, “Looky Looky,” a fluffy cream puff of a pop song. A YouTube clip of Moroder performing the number for a French TV Show called Musicolor stands as proof that he was anything but a showman. His voice is unremarkable, his hairline already receding, his face half obscured by his cartoonish mustachio, as he gawkily sways to and fro, flaunting an absurdly long ascot that looks as if it’s been splattered in amoebas. He’s no rock star. He’s like the drunken uncle you wouldn’t invite to your wedding for fear of what he’d do at the reception.

It was the classical composer Eberhard Schoener who gave Moroder his first tutorial in the Moog synthesizer. His 1972 album, Son of My Father, already bore traces of the electronic-based disco that would become his calling card — a remake of its title track, by the British pop group Chicory Tip, was the first U.K. number 1 single to prominently feature a synth. Three years later, inspired by the minimal soundscapes of his peers Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, Moroder confected his own electronic record, Einzelgänger, a hypnotic, space-age reverie that sounds shockingly ahead of its time.

Not shockingly, Einzelgänger was a commercial flop. But Moroder could afford to take the risk — later that year he’d release the song that would launch his and Donna Summer’s careers.

“She was not comfortable singing ‘Love to Love You Baby,’” Moroder says of the hit track, which the BBC once estimated contains 23 simulated orgasms. “It’s quite amazing she did it, because she was not somebody totally outspoken.”

Moroder and Pete Bellotte met Summer, a Massachusetts-born expat and at the time a musical theater performer, when she was doing session work at Musicland. The trio had a minor hit abroad with Summer’s debut album, Lady of the Night, but she was still unknown in the U.S. when they sent a tape of “Love to Love You Baby” to Casablanca Records president Neil Bogart, who loved it so much he asked them to lengthen it. The result, which clocked in at nearly 17 minutes, is the embodiment of late-’70s New York: slick, celebratory, trance-inducing, excessive, smutty, relentless.

“I don’t really remember how I told Donna, ‘Now let’s do the moaning,’ but she did it,” Moroder says. “She had a little problem because her husband was there in the studio. So I said, ‘Let’s save this song.’ I threw everybody out.” In interviews, Summer told journalists she imagined herself as Marilyn Monroe while she continually feigned climax on the floor in total darkness.

Those orgasms reverberated across dance floors and airwaves worldwide. The track was Summer’s first to crack the U.S. Top 40, and it topped the Billboard disco chart for four weeks. But it wasn’t a hit with everyone. “Her parents did not like it,” Moroder says. “I remember I met them once, and they were not happy with me. They thought I was the devil corrupting their beautiful girl. I didn’t say anything, but I thought, Why is she riding in a limo?” He chuckles. “The devil made her ride in the limo.”

Moroder and Summer continued their winning streak, banging out a string of concept albums in rapid succession, including 1976’s A Love Trilogy and Four Seasons of Love and 1977’s I Remember Yesterday, a journey through time that whirled from the sounds of the 1920s into the future. The record featured what is widely considered Moroder’s greatest coup: “I Feel Love,” the first-ever entirely synthesized disco track, and arguably the most important of the entire genre. (It inspired Moroder to release his two seminal solo albums, 1977’s From Here to Eternity and 1979’s E=MC² — both continuous, vocoder-heavy dance parties also made entirely on synthesizers.)

With its chugging, repetitive bass line, glimmering arpeggios, and undulating key changes, “I Feel Love” still sounds light-years away. Upon hearing it, Brian Eno famously told David Bowie that the single was “going to change the sound of club music for the next 15 years.” Or 40. It has since become a gay anthem.

Moroder can’t really fathom the resonance tracks like “Love to Love You Baby” and “I Feel Love” have had with gay listeners. When I ask why he thinks Summer became a gay icon, he turns the question back on me. “Why do you think she appealed so much to gays?” I tell him that many gay men growing up then felt marginalized and inhibited, and that she served as a sort of beacon, a symbol of unbridled sexuality and liberation.

He nods, sipping his cappuccino and pondering this for a moment. The producer then goes on to explain that Bogart was actually quite calculated in his marketing of Moroder’s solo work through Casablanca Records, particularly his 1976 album, Knights in White Satin, the entire first side of which consisted of a goofy disco remake of the Moody Blues song “Nights in White Satin.” Its cover art, which boasts five open-shirted men dressed in white, bent down on their knees and staring longingly up at Moroder in what appears to be a steamy Turkish bathhouse, is hardly subtle. For added homoerotic subtext, before the album was released, and unbeknownst to Moroder, Bogart added a “K” before the “Nights” in the title of the record and lead track. Moroder didn’t notice until months later.

“He was pushing me to be ‘gay,’ ” Moroder says. “I think he recognized quite fast that disco could appeal to gays. When ‘Love to Love You Baby’ came out, it was immediately a hit in discotheques, because people could dance to this repetitive rhythm, get into a trance.”

Moroder, Bellotte, and Summer would record four more studio albums together — 1977’s Once Upon a Time, 1979’s Bad Girls (featuring the classic title track and “Hot Stuff”), 1980’s The Wanderer (their first with Geffen Records), and 1981’s I’m a Rainbow (shelved until 1996) — before parting ways.

“She went to Geffen and started to become much more religious,” Moroder recalls. Summer’s beliefs were clearly at odds with her gay-icon status, though she denied ever making antigay statements. “The last two albums we did, I was not really happy with her,” Moroder says. “She didn’t want to sing this line because there was this word. She wanted to sing a song about Jesus. What can you do? She was my main singer.”

The two lost touch until 2010, two years before Summer died of lung cancer. Moroder had moved to Los Angeles, while Summer had been living in Nashville and Florida. She reached out to Moroder, saying she was interested in moving to L.A., so he invited her to his high-rise in Westwood. She loved the building so much that she rented the apartment directly below his. They were in frequent contact and tossed around ideas for a reunion tour, but nothing ever came to fruition.

Only Summer’s immediate family knew of her illness, but Moroder and his wife, Francisca, suspected she was sick. “About six months before she died, she sent me a letter and really thanked me — not just ‘thank you,’ but ‘you changed my life,’ ” he says. Moroder and Summer saw each other more in those two years than they had in the two-plus decades after they stopped recording together. He fondly remembers Summer overhearing him through the floor one day when he was tinkering with his keyboard. “After 10 minutes or so, she called and said, ‘Giorgio, what did you play? It was great!’ ” he says. “I was just improvising.”

Before Daft Punk helped yank him back into the spotlight, Moroder was living the leisurely life of a typical retiree: crossword puzzles, a bit of travel, a lot of golf. Now everything has changed.

Signing with RCA Records, a division of Sony, helped him secure an impressive lineup for his new album. Of the material that made the final cut, Moroder’s favorite is the title track, which features vocals by Sia, these days herself an in-demand producer. “Déjà Vu” splits the difference between the soaring, rafter-shaking club-pop we’ve come to expect from the Aussie singer and Moroder’s 1970s trademarks: a noodly funk-guitar line, an irresistible four-to-the-floor beat, melodramatic strings, saucy handclaps. It’s an exuberant disco banger that would make Donna Summer proud, and if there’s justice in this world, it will be the song of the summer.

His collaboration with Britney Spears is more of a head-scratcher. It’s a remake of folk singer Suzanne Vega’s 1987 a cappella song “Tom’s Diner,” a track that became a hit when it was remixed by the British dance duo DNA in 1990. But Moroder was thrilled to resurrect it. “Britney asked if I was interested in doing a recording with her,” Moroder says, his eyes widening. “You know, to record with Britney after 30 years? That’s quite interesting, to say the least. So I said yes.”

Déjà Vu’s lead single, the Kylie Minogue-fronted “Right Here, Right Now,” shimmies through a sea of cascading synths to a cloud-parting siren’s call of a chorus, while Charli XCX’s contribution, “Diamonds,” gallops along a rubbery bass line as the singer does her scrappy-decadent shtick. Charli wrote the track as a teen, but couldn’t make it work for her first album. When she sent it to Moroder, however, he jumped on it. “When Giorgio asked me to be a part of this record, I was so honored,” Charli says. “We haven’t met — we just worked over email. But I was excited from the beginning. He is such a legend.” Both songs, along with the raging, mostly instrumental “74 Is the New 24,” come decked out with one of Moroder’s oldest (and most imitated) tricks: vocoder effects. Overall, the tracks that feature guest vocals sound like the music of their vocalists. Yet considering that everything on the radio now sounds sweeping and digitized and roboticized within an inch of its life, that really just means that they sound like Giorgio Moroder songs.

Still, the music industry is different now. There are Twitter followings and Vimeo impressions and huge teams with huge opinions. Moroder doesn’t always feel cool. Or maybe he feels too cool, but knows what he has to do to play the game. “This business is quite complicated,” he says. “If you read the credits of big number 1 songs, there are five, six, seven composers and a minimum of two producers. Now I understand. I tried to keep it to a minimum because you don’t really need six people to do it. And if somebody comes in with a little, ‘Ah ah ah, ooh, ooh, ooh,’ that doesn’t mean he’s suddenly a lyric writer. That whole environment — that was my biggest problem.”

Does he feel like the album has enough of the Moroder stamp on it? “Yeah, because in the end it’s my work,” he says. “The arrangements — they’re all mine.”

Moroder toured with Minogue in Australia in March and will continue to DJ this year to support Déjà Vu. He’s also partnering with Skrillex on the soundtrack for Disney’s new Tron video game. At one point the producer was working with a major management company to mount a recurring Las Vegas DJ show called A Night With Giorgio Moroder. An attempt to re-create Studio 54, the party was set to include a disco ball and dancers in cages, with Moroder spinning ’70s tracks into the small hours. He was hoping to get Cirque du Soleil involved and turn it into an international franchise — “a bit like Blue Man Group,” he told The Guardian. But the project never really took off. Perhaps that type of tentpole nostalgia just isn’t cool right now.

“The problem was the company wanted to commit to only one or two shows, and that was too risky,” Moroder says. “Because if the show is great, perfect. If it’s not great, I’m dead in Vegas.”

“So now,” he continues, “we’re going to wait until I have a few major hits.”