Complex

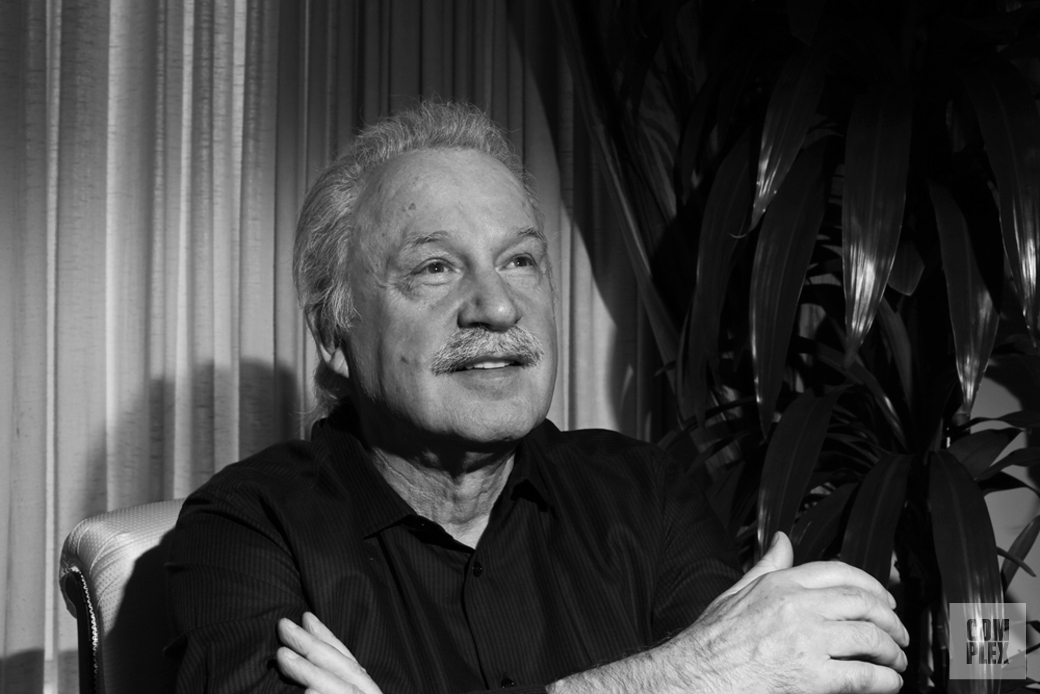

The Future Is Now: Giorgio Moroder Predicted Today’s Pop Music 40 Years Ago

By Brendan Frederick

Photography by Chuck Grant

June 16, 2015

Synthesizers pump through the heart of contemporary pop music, but in the early ’70s, machine-made music seemed like a sci-fi fantasy. That is, until 1976, when disco queen Donna Summer recorded her single “I Feel Love,” a worldwide smash hit composed by producer Giorgio Moroder using Moog synths. It was disco that sounded like it was from the future. Today, it’s seen as the big bang of modern music: the birth of synthpop, EDM, and all of today’s electro-infused genres.

Before evolving the global disco scene, the Italian-born Moroder made his name in German pop music. After his breakthrough, he moved to Hollywood and scored some of the biggest films of the 1980s, including Scarface, Flashdance, Top Gun, and The Never Ending Story, racking up Oscars like Meryl Streep along the way. Moroder’s innovation opened the door for a generation of electronic producers and pop impresarios—from Trent Reznor to Pharrell Williams—to score major Hollywood films.

After retiring from public life in the early ’90s, Moroder reemerged in 2013 on Daft Punk’s Grammy-winning album Random Access Memories, where the group acknowledged him as a major influence on the song “Giorgio by Moroder.” Since then, he’s been DJing stadiums and clubs around the world while recording Déjà Vu, his first album in 30 years, with an all-star cast of collaborators, including Britney Spears, Sia, Charli XCX, and Kylie Minogue. With plans to work on Lady Gaga and Lana Del Rey’s next albums, it’s clear that Moroder still has a finger on the pulse and an eye on the horizon.

You’ve created so many classic dance records. Are you good at dancing?

No, I am the worst. My wife is one of the best dancers and I’m terrible, so she dances for me. I always felt—even when I was in the discotheque—that you have to dance a lot to get that feeling of not looking embarrassed. So, I never really learned. But I tap my feet quite well.

Donna Summer was known as the queen of disco. Who do you think is the queen of today’s pop music?

Well, you have the big ones like Lady Gaga and Rihanna. They have good songs. And then there are some rappers—Iggy is big now, but I don’t know how long she’ll last. Today, it’s not only singing, it’s the acting, the way you dress, what you represent. With Donna, it was only songs. Now it’s songs, fashion, and movies. It’s much more complex now.

It must be exciting to release your first album in 30 years. What kind of sound did you want to come back with?

Well, ideally, a sound like the song I did with Sia [“Déjà Vu”]. I have some electronics, like the arpeggio bass line, but then also a little bit of a disco, retro feel. So, I have a guitar, I have strings, I have a Fender Rhodes. Since I was, let’s say, one of the co-inventors of disco, and a little bit of a co-inventor of electronic music, I thought I should combine the two sounds.

You’ve released many albums, but this is the first time you’ve assembled an all-star lineup of collaborators. Why didn’t you make an album like this in the ’70s or ’80s?

At the time of Donna Summer’s success, I could have had other people sing on my albums instead of me, but it was something nobody did. There was not that kind of collaboration back then. One of the first ones to do it was Santana [on 1999’s Supernatural], when he played his instrumental with other voices. When the music started to sell less, people were more willing to sing songs with somebody else or for somebody else. Now some of the major acts come out every two months with a single. Everything has changed so much.

The $7.2 million lawsuit that Marvin Gaye’s family won over “Blurred Lines” caused a lot of controversy. As someone whose work influenced so many artists, do you think the verdict was fair?

There was an article saying, “How would music have progressed if Giorgio Moroder would not have allowed Daft Punk to play his samples?” and all this stuff. So, I was jokingly thinking, I could sue everybody who played that kind of a bass line, from 1976 up to now. There were probably 1,700 songs with a similar bass line. I would be almost a billionaire! [Laughs.] But I’ve never sued anybody since I’ve been in the business. I might if it’s a little closer to the original, like I think there was one Madonna song [2005’s “Future Lovers”] where there was the same bass line and they changed just one note. But if they go only by the “feel” of the song, then every composer is going to have a big problem. I probably was influenced by some similar stuff before me. It’s an evolution, and you cannot stop it.

It was great seeing you on stage last year at the Grammy Awards with Daft Punk. Why did it take so long for the Grammys to recognize the impact of the electronic genre you helped start?

There was no one act to do it consistently and well. Before Daft Punk there were some commercial groups—you had [Brian] Eno and some others—but Daft Punk has been around for a long time, and they did so many records and they built up an incredibly good image. I had been interested in them since I heard “One More Time,” one of my favorite songs. And this time, the whole product was so good. “Get Lucky” was such a big No. 1 song, and it reflected so much of the contemporary sound, but still has that great disco feel. If the product was not so good, and they were not such icons, it could have never gotten the Grammy.

One of your best soundtracks was Scarface. What was the process of scoring that movie?

When I met with the director Brian De Palma in New York, he told me about the movie and gave me the script. You had this character at the beginning who is a happy guy who made it to America, but then he gets into all kinds of problems with drugs. I went back to Los Angeles, and I composed a song even before I saw any scenes. And Brian liked the demo I did. I gave it that dark, hammering note—dong, dong, dong—to capture that feel of desperation. Sometimes, if you have the main theme done, then the rest is all relatively easy.

Kanye West sampled the Scarface theme and also, coincidentally, worked with Daft Punk. Are you familiar with Kanye’s music?

I like him. What I like about Kanye’s stuff is he always comes out with new sounds that are totally different. When I heard “Mercy” about two years ago, I said, “What a weird song, and what an interesting sound.” The part when he sampled [“Tony’s Theme”] was quite clever because he took just those two chords, instead of sampling the whole phrase, which gave it that special sound. He did a good job with that one. And even the last song he did with Rihanna and Paul McCartney [“FourFiveSeconds”]—he’s inventive. I’m less connected to all his other affairs aside from music—calling himself the god of creativity and all that stuff. But he’s really good.

You’ve been involved in many things outside of music and film, from designing a ridiculously expensive supercar to creating computer-generated art. Which of your extracurricular activities have you enjoyed the most?

Well, certainly one was the [Cizeta-Moroder] car, which was something totally different for me. I helped a little bit with the look of it—certainly nothing like the technical aspects. We sold about eight or nine cars before the world economy collapsed in ’91 or ’92. It’s a beautiful car. I still have the prototype, but I cannot drive it because it’s not legal. I may want to [modify] it so I can drive it again, but, you know, driving a million-dollar car—or whatever it’s worth—on the freeway, and something happens? I don’t want to be in that situation. But maybe one day I’m going to get it on the road.

For many years, you were known for your mustache, until you shaved it off sometime in the ’80s. What made you decide to finally grow it back?

When Daft Punk came out, people said, “Oh, this is Giorgio, OK—but you look strange. You look much better with a mustache!” So, finally I said, “OK, let’s go back.” I don’t know if you notice, but it’s much smaller. Much more up to the 21st century.

Forty years ago, you created music that sounded like the future. What do you think music will sound like 40 years from now?

I don’t have a clue! Sound-wise, I don’t think there’s anything new to find, because there’s millions of sounds you can find with one synthesizer. Maybe it’s more about the combination of music, like how rap established something totally new. It’s probably more like an attitude to the music or the way the vocals are. But I don’t know. If I knew—if you could give me a hint—I would be so happy.